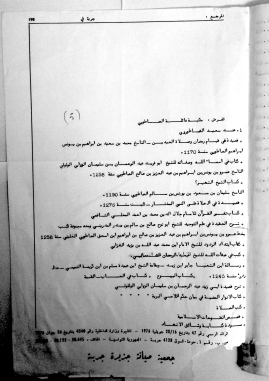

Figure1 : The first and only remaining page of the typewritten hand list of the al-Ṣāṭūrī library (Original held in the ASIDJ in Houmet Souk, Jerba)

Over the past several years, I have worked with private manuscript collections belonging to families in Jerba, Tunisia. The island is home to several well-known libraries, including those belonging to the Barouni (al-Bārūnī), Ben Yagoub (Bin Yaʿqūb), El Bessi (al-Bāsī), and Batour (al-Baʿṭūr) families. A lesser-known but equally important collection belonging to the Satouri (al-Ṣāṭūrī) family of the area of Beni Maagal also held (holds?) and important and fascinating collection of texts. A systematic study of the library and its history remains to be done but in this post I’d like to offer a few hints at its history.

First and foremost, it deserves mention that the Satouri family historically belonged to the Mistāwa community of Ibadis in Jerba. This community, pejoratively but more commonly known as “Nukkārīs” (hence the scare quotes in the blogpost title), represents an alternative form of Ibadism in northern Africa. [1] The Satouri family was prominent in Jerba throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, with strong connections to the Bey and, after 1881, the colonial French government. [2] Like many former Mistāwa families in Jerba, the Satouris converted to Mālikī Sunnism sometime in the modern period. [3]

As is the case for so many other libraries in Jerba, the history of the Satouri collection has to be strung together from mostly unverifiable oral accounts and snippets of information drawn from archives. For example, I recently spoke with someone who told me that he had seen the library in the 1980s and had helped rearrange its contents. This person also mentioned there being an Amazigh-language text in the collection, which would make sense since some Mistāwa communities of Jerba were (and are) speakers of local Amazigh-language dialects (collectively called shilḥa by Arabic speakers on the island).

On the archival side of things, we fair a bit better. No colonial-era archives mentioning the collection survive to my knowledge, although the family does have a paper trail since many of them worked as notaries and other official positions in the early-20th century [4]. Like the Baʿṭūrī library, we are lucky to have the al-Ṣāṭūrī collection included in a survey of libraries published in 1987 by a local cultural association. Unfortunately, only the first page remains (sigh). [5] Nevertheless, it is an important page! (Figure 1)

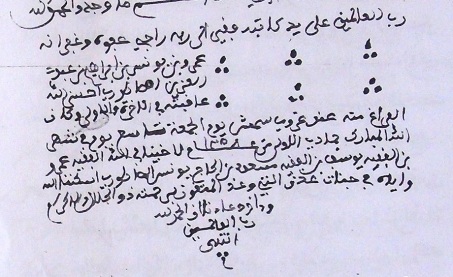

Figure: 2 Photocopy of a colophon of a manuscript in hand of ʿAmr b. Yūnis b. Ibrāhīm b. ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Ṣāṭūrī (date 9 Jumāda al-awwal 1258 / 18 June 1842).

First, it begins with a subheading noting that this page lists books belonging specifically to Saʿīd l-Sāṭūrī, who presumably is a living member of the family (or at least was in 1987). The collection may have been divided among different members of the family on subsequent pages.

The page is also important for what it tells us about the Satouri family’s history. Several texts, dating to the 12th/13th centuries AH (18th/19th CE) are listed with members of the family as their copyists. These cover an entire century, beginning in 1170AH and ending in 1276AH. I’m currently preparing a short annotated version of this first page along with references to the Satouri family in the archives and a handful of manuscripts.

As for the latter, there is even more promising evidence to compliment what survives in the hand list. The Association pour la sauvegarde de l’île de Djerba (ASIDJ), responsible for making the hand list in the first place, also houses scans of photocopies of several manuscripts originally held in the Satouri library. The copyists and titles of these some of these texts appear to be the same as those given in the hand list.

For example, the copyist of several manuscripts in a majmūʿ appears as “ʿAmr b. Yūnis b. Ibrāhīm b. ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Ṣāṭūrī” and dates to 9 Jumādā I 1258AH (18 June 1842). The same copyist and date appear in the hand list as part of a majmūʿ (Figure 2). The titles are no less important, since many are connected to ʿAbd al-Allāh b. Yazīd al-Fazārī (d.3th/9th c.), recognized by historians as an important and influential figure for Mistāwa Ibāḍīs. [6]

It will take a bit of detective work, but my guess is that most of the texts in the hand list with al-Sāṭūrī copyists are in this collection of photocopies. More on all of this soon.

خلال السنوات الماضية، تعاملت مع عدّة مكتبات خاصة تملكها عائلات في جزيرة جربة في تونس. توجد في هذه الجزيرة الكثير من المكتبات ذات شهرة ومن ضمنها المكتبة البارونية ومكتبة الشيخ سالم بن يعقوب ومكتبة جامع الباسيين والمكتبة البعطورية. بالإضافة إلى تلك المكتبات، توجد مكتبة غير معروفة كثيرا ولكنها مهمّة أيضا وهي مكتبة عائلة الساطوري (أو الصاطوري كما يظهر الاسم أحيانا) في منطقة بني معقل. كانت (وما زالت؟) لهذه المكتبة مجموعة مهمّة من المخطوطات ولكنّ دراسة أكاديمية حول تاريخها لم تُكتب بعد. أقدّم هنا بعض الملاحظات والتلميحات إلى تاريخ هذه المكتبة.

قبل كل شيء، علينا الإشارة إلى أنّ عائلة الساطوري تاريخا انتمت إلى الإباضية “المستاوة” في جربة. تُعرف هذه الجماعة باسم آخر وهو “النكّار” ويمثّلون تعبيرا آخر لمذهب الإباضية في شمال إفريقيا. [1] كانت عائلة الساطوري بارزة في المجتمع الجربي خلال القرنين التاسع عشر والعشرين وكانت لها روابط قوية بالسلطة المركزية في تونس قبل وصول المستعمر الفرنسي وبعده. [2] شأن العائلة شأن الكثير من العائلات المستاوية في جربة بما أنّهم تحوّلوا من إباضية إلى مالكية في العصر الحديث. [3]

مثل أغلبية المكتبات الجربية، علينا محاولة بناء السرد التاريخي للمكتبة الساطورية من خلال جمع حكايات شفوية غير مؤكّدة وبعض الوثائق الأرشيفية والعائلية. على سبيل المثال، تحدّثت أخيرا مع أحد سكّان الجزيرة قال لي إنّه رأى المكتبة في الثمانينات من القرن الماضي وساعد في إعادة ترتيب رصيدها. ذكر أيضا وجود مخطوط بللغة الأمازيغية في المكتبة وهذا معقول جدا بما أنّ المستاوة في جربة تاريخيا وحاليا ناطقون باللهجات الأمازيغية (معروفة بـ“الشلحة” بين الناطقين بالعربية في الجزيرة).ـ

من ناحية الأرشيف، لم أتعثر على وثائق تذكر المكتبة ولكنّ العائلة الساطورية (أو “الصاطورية” كما تظهر في الوثائق) مذكورة في بعض الملفات الأرشيفية من العصر الاستعماري من القرن العشرين [4]. ومثل المكتبة البعطورية، لدينا جرد من رصيد المكتبة قامت بتحضيره جمعية صيانة الجزيرة في عام ١٩٨٧. للأسف، تبقى الصفحة الأولى فقط [5] (انظروا صورة ١). مع ذلك، فإنّها صفحة مهمّة!ـ

أولا، يوجد في أول الصفحة ذكر لصاحب هذه المخطوطات وهو سعيد الساطوري، الذي كان فردا حيا من أفراد العائلة آنذاك. للجرد أهمية أخرى وهي ماذا تقول عن تاريخ العائلة. مثلا، تظهر أسماء أفراد العائلة نسّاخا للمخطوطات المؤرّخة من القرنين الثامن عشر والتاسع عشر الميلادي، بداية من ١١٧٠هـ ونهاية من ١٢٧٦هـ. أقوم حاليا بتحقيق هذه الصفحة إضافة إلى جمع إشارات إلى تاريخ العائلة موجودة في الأرشيف التونس وبعض المخطوطات الخاصّة.

فيما يتعلّق بالمخطوطات، توجد نسخ إلكترونية من عدة مخطوطات كانت في المكتبة الساطورية وبعض أسماء النساخ والمؤلفين هي نفس الأسماء الموجودة في الجرد. مثلا، يظهر اسم نفس الناسخ في عدّة مخطوطات وهو“عمرو بن يونس بن ابراهيم بن عبد العزيز الساطوري” (مؤرّخ ٩ جمادى الأول ١٢٥٨ هـ الموافق بـ١٨ جوان ١٨٤٢). يظهر نفس الناسخ ونفس التاريخ في الجرد (انظروا صورة ٢). للمخطوطات المصوّرة والمذكورة في الجرد أهمية أخرى وهي مؤلف بعضها: عبد الله بن يزيد الفزاري (ت ق٣/٩) الذي يعتبر من أهمّ الشخصيات تأثيرا على الإباضية المستاوة [6]. ـ

يأتى المزيد فيما بعد إن شاء الله!ـ

—

Notes

[1] Nukkār literally means “the deniers,” which traditionally has been interpreted as meaning those who refused to acknowledge the second Rustamid Imam of the 8th century, ʿAbd al-Wahhāb b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Rustam (d.749). For a summary of the traditional story, see P. Love, “Djerba and the Limits of Rustamid Power,” Revista al-Qanṭara 33:2 (2012), esp. 305-309.

[2] Several files connected to the al-Ṣāṭūrī family are today held in the Archives Nationales de Tunisie, ranging in time from 1900 (FPC / B1 / 0218 / 002 0025) to 1956 FPC / D / 0088 / 0023 005). In the archive’s database, the name is spelled with a sīn rather than a ṣāḍ.

[3] Tunisian historian Mohamed Meriami wrote a fascinating piece on the Satouri’s transition from Mistāwa to Mālikiyya, drawing on both oral histories and family archives: M. Meriami, “al-Dhākira al-ʿāʾiliyya wa-wāqiʿ majmūʿat Mistāwa fī jazīrat Jarba khilāl al-qarnayn 18 wa-19” IBLA 190 (2002), 47-78.

[4] For examples, see note 2 above.

[5] “Maktabat ʿāʾilat al-Ṣāṭūrī,’ in Qāʾimat al-kutub al-mawjūda fi-l-maktabāt al-khāṣṣa wa l-ʿāmma (Hūmat al-sūq: Jamʿiyyat ṣiyānat jazīrat jarba, 1987)

[6] On whom see A. al-Sālimī and W. Madelung, eds., Early Ibāḍī Theology (Brill, 2014), 1-7.