Last summer, in a series of email exchanges, colleagues Dr. Aurélien Montel (Maître de Conférence, Université Toulouse – Jean Jaurès) , Mr. Soufien Mestaoui (Director, Ibadica), and Dr. Michael Erdman (Head, Middle Eastern & Central Asian Collection, The British Library) together identified an exciting copy of the Maghribi Ibadi tafsir, known as the Tafsīr Hūd b. Muḥakkam al-Hawwārī (d. late 3rd/9th c).1 The manuscript merits attention because the various stages of its social life, from production to provenance, together summarize key aspects of the history of Ibadi communities in the Maghrib.

في السنة الماضية، من خلال التواصل عبر الإيميل، وصلوا الزملاء د. أوراليون مونتال (جامعة تولوز) و أ. سفيان المستاوي (مركز ايباديكا) و د. مايكال اردمان (المكتبة الوطنية البريطانية) إلى التعريف بنسخة مخطوطة من التفسير الإباضي المغاربي المعروف بالعنوان “تفسير هود بن محكّم الهواري” (ت ق3/9). يستحق المخطوط بالاهتمام لأنّ مراحل حياتها الاجتماعية تلقي الضوء على تاريخ المذهب الإباضي في شمال إفريقيا

The copy is fascinating for a few different reasons, not the least of which is the general rarity of copies of the tafsīr.2 Indeed, it is probably unique among the extant premodern Ibadi tafsīrs written in the Maghrib and the genre itself is uncommon among Ibadis compared to many other intellectual traditions in Islam. That the text was written so early and is attributed to a Maghribi author drawing on eastern traditions from the previous century makes it a remarkable snapshot of early Ibadi intellectual history in North Africa.3

تثير هذه النسخة للاهتمام لأسباب عديدة وليس أقلّها ندرة نسخ مخطوطة من التفسير. فعلا، تفسير هود قد يكون فريدا من نوعه لأنّ التفاسير الإباضية الأخرى من شمال إفريقيا اندثرت ولم تبقى منها إلا إشارات غير مباشرة في نصوص أخرى. نظرا لعمره المبكر، تفسير هود يوفّر لنا نافذة على الفكر الإباضي في المغرب في العصور الإسلامية الأولى

The Bin Mashīshī’s: A Family of Copyists | بن مشيشي: عائلة النسّاخ

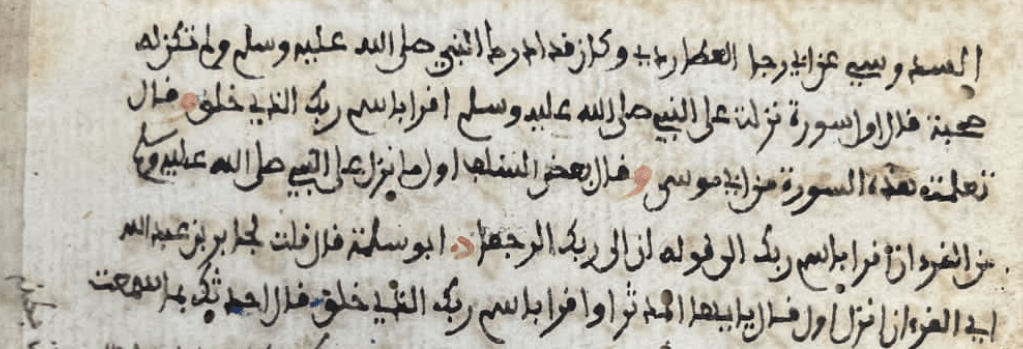

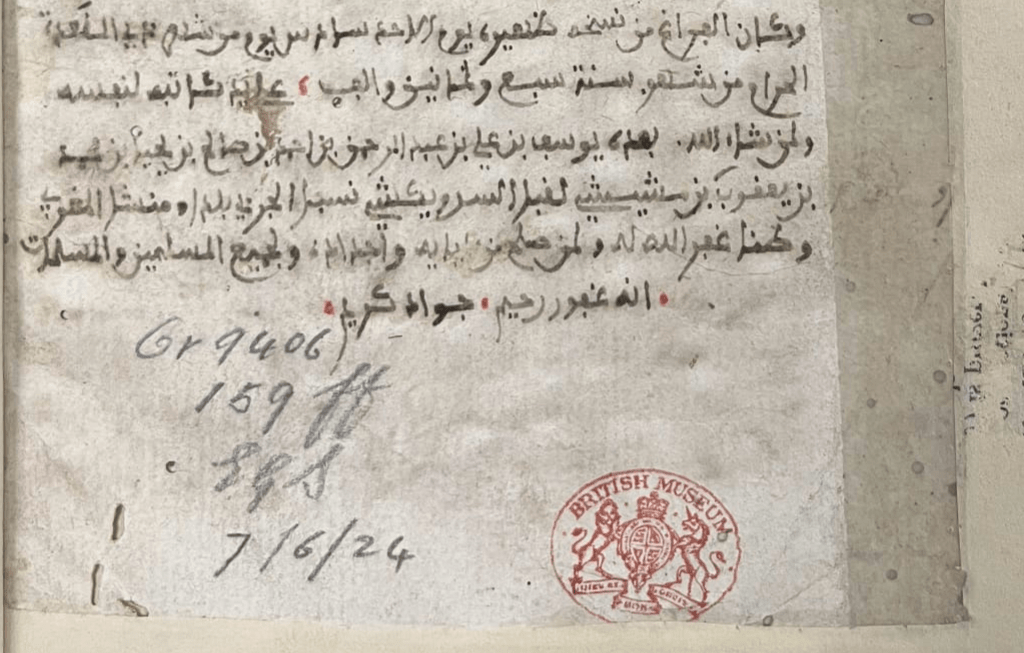

Also noteworthy, the manuscript is in the hand of a known copyist from the area of Sidwīkish on the island of Djerba, Tunisia, active in the 11th/17th century: Yūsuf b. ʿAlī b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Aḥmad b. Ṣāliḥ b. Yaḥyā b. Muḥammad b. Yaʿqūb b. Mashīshī al-Sidwīkshī. The colophon gives his full name (below).

جدير بالملاحظة أيضا أنّ المخطوط بخط يد ناسخ معروف أصله من منطقة سدويكش في جزيرة جربة (تونس) في القرن 17/11 وهو يوسف بن علي بن عبد الرحمان بن أحمد بن صالح بن يحيى بن محمد بن يعقوب بن مشيشي السدويكشي، كما هو يعطي اسمه ونسبه في آخر المخطوط (انظر الصورة)

Other manuscripts in his hand include three copies of books of the Ibadi fiqh compilation known as the Dīwān al-Ashyākh, today housed at the El Barounia library in Djerba.4 That Mashīshī was copying the text some six centuries after the tafsīr‘s compilation shows the text’s importance within the Maghribi Ibadi communities throughout the medieval centuries and into the early modern era. The colophon notes that the copyist is both from Djerba and Maghribi. When an Ibadi copyist mentioned these details in the 17th century, it often meant that he was neither in Djerba nor the Maghrib at the time of transcription. Instead, Bin Mashīshī may well have been studying in Egypt at al-Azhar and living at the “Buffalo Agency”, or Wikālat al-Jāmūs. This the trade agency, school, and library was run by Ibadis from the 17th to the early 20th centuries in Cairo and is the subject of my recent book.5

توجد مخطوطات أخرى في خطّ يده من ضمنها ثلاث نسخ من أبواب من “ديوان الأشياخ” (أحد أهم المدوّنات الفقهية عند الإباضية) وهي توجد اليوم في المكتبة البارونية في جربة. اهتمام يوسف بن مشيشي بنسخ هذا النص بعد تدوينه بستة قرون يدلّ على أهميته للمجتمع الإباضي المغاربي خلال العصرَين الوسيط والحديث. يذكر الناسخ بأنّه مغربي و من جربة وغالبا ما يذكر النسّاخ هذه المعلومات (أي النسبة والأصل الجيوغرافي) عندما لم يكونوا في جربة ولا في المغرب. الأرجح أنّه كان ينسخ المخطوط في مصر حيث كان توجد جالية كبيرة من الإباضية المغاربيين يدرسون في جامع الأزهر ويسكنون في وكالة الجاموس. كانت توجد هذه الوكالة التجارية ومدرسة ومكتبة في القاهرة لمدّة أكثر من ثلاث قرون وهو موضوع كتابي الأخير

Copying was, moreover, a family tradition for the Mashīshīs. Yūsuf’s brother Muḥammad copied a manuscript (dated 1 Muḥ 1037/ 12 Sep 1627) today housed in the library of the Djerban historian Shaykh Sālim Bin Yaʿqūb (d.1991).6 Muhammad’s son, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Mashīshī, copied a manuscript that used to be in the private collection of Saʿīd b. Qāsim al-Shammākhī (d.1884) and is now housed in a private library in Oman, as well as another manuscript today found in the Bibliothèque Nationale de Tunisie .7 Finally, ‘Abd al-Rahman’s grandson, Saʿīd b. Sulaymān b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Muḥammad b. ʿAlī b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Mashīshī(!) copied two texts of his own in the 1182/1768.8 Those manuscripts, and all four Mashīshī copyists, were connected to the Wikālat al-Jāmūs.

كان نسخ المخطوطات فعلا عادة موروثة في عائلة بن مشيشي الجربية ونجد أسماء عدّة أفراد عائلة يوسف في مخطوطات كثيرة. مثلا، كان ليوسف أخ اسمه محمد ونسخ كتابا يوجد اليوم في مكتبة الشيخ سالم بن يعقوب (ت1991) في جربة. ابن محمد، عبد الرحمان بن مشيشي، أيضا نسخ المخطوطات ومنها مخطوط في مكتبة خاصّة في عُمان ومخطوط آخر يوجد اليوم في المكتبة الوطنية التونسية. حتى حفيد عبد الرحمان وهو سعيد بن سليمان بن عبد الرحمان بن محمد بن علي بن عبد الرحمان بن مشيشي(!) كان ناسخا للكتب. وكانت لكلهم الأربع علاقة بوكالة الجاموس

An Unexpected Owner | مالك غير متوقّع

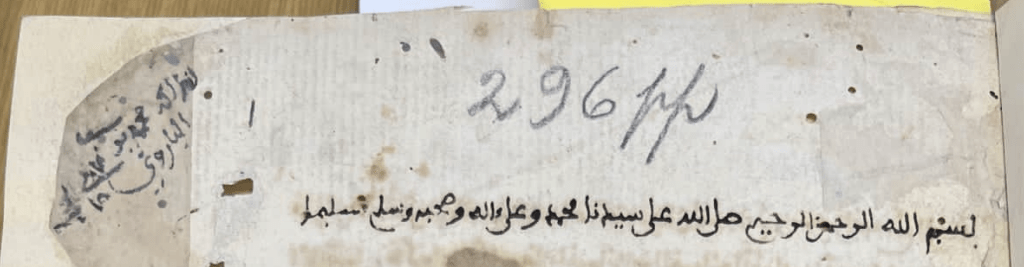

Another interesting thing about this manuscript, which reveals another chapter in its social life, is the ownership statement in the top left corner of the first folio. It attributes the manuscript to Muḥammad b. Yūsuf al-Bārūnī (d. 1920s), who was the founder of the first Ibadi print house in Egypt, the Bārūniyya Press (al-Maṭbaʿa al-Bārūniyya), which operated from around 1870 into the beginning of the 20th century.

نقطة أخرى تستحق بالذكر بيان الملكية (أو التمليكة) الموجود في أعلى يسار الورقة الأولى، وهي تدلّ على أنّ المخطوط كان ملكا لـمحمد بن يوسف الباروني (ت بعد 1920). كان محمد بن يوسف مؤسّس المطبعة البارونية، وهي المطبعة الإباضية الأولى. تأسّست عام 1870م واستمرّت في الطباعة حتى بداية القرن العشرين

Al-Bārūnī was an Azhari-turned-entrepreneur, who started the Press with colleagues from Algeria and his homeland of the Jebel Nafusa in what is today Libya. The Bārūniyya Press printed Ibadi authored and non-Ibadi-authored lithographs and eventually typeset printed books. Muḥammad al-Bārūnī, like all other actors in this manuscript’s social life, was also linked to the Buffalo Agency. From the early 20th century until around 1914, he directed the endowments (awqāf) of the Agency, which supported the students who lived there.9

كان محمد الباروني طالبا في الأزهر ولكنّه قرّر أن يتبع المسلك التجاري عندما أسّس المطبعة مع شريكَين من وادي المزاب وجبل نفوسة. خرجت من المطبعة البارونية كتب إباضية وغير إباضية واشتملت طبعات حجرية وحديثة. كانت لمحمد الباروني أيضا علاقة بوكالة الجاموس لأنّه بدأ يحمل المسؤولية عن إدارة أوقافها حول 1914م

From Cairo to London | من القاهرة إلى لندن

The book was acquired by the British Library in 1924 from the book dealer Isaac Benjamin Yahuda. Yahuda was a book dealer in Cairo and his younger brother, Abraham Shalom Yahuda (d.1951), offered large numbers of manuscripts to the British Library.10 The two also sold books that were acquired by the University of Michigan, Princeton, Yale, and other libraries.11 The timing is just about right for the manuscript to have been acquired directly from Muḥammad al-Bārūnī himself, who died around 1927. Muḥammad knew other orientalists in Cairo who also collected manuscripts and Ibadi lithographs, like Zygmunt Smogorzewski (d.1931) and probably also the Italian intelligence officer, Enrico Insabato (d.1963), who was based for some time in Cairo.

انتقل المخطوط إلى المكتبة الوطنية البريطانية في 1924 بشراء من تاجر في الكتب اسمه اسحاق بنيامين يهودا. كان تاجر في الكتب في القاهرة وأخوه الصغير ابراهام شلوم يهودا (ت1951) باع مخطوطات كثيرة إلى المكتبة البريطانية والأخوان باعا كتبا أخرى إلى جامعات أمريكية منها ميشيغان وپرينستون ويايل وغيرها. فترة الشراء (أي 1924) تشجّع الافتراضية بأنّ المخطوط جاء مباشرة من محمد الباروني نفسه خاصّة والباروني قد عرف مستشرقين آخرين اشتروا مخطوطات وكتب إباضية مثل زيغمونت سموغورسفسكي (ت1931) وممكن أيضا الضابط الإيطالي انريكو انساباتو (ت 1963) الذي سكن في القاهرة لمدّة طويلة

From its content, to its copyists, to its travel, to its provenance, this manuscript encapsulates in one volume much of the story of Ibadi intellectual traditions and manuscript histories from the past four centuries.

باختصار، في مجلّد واحد يحمل هذا المخطوط مقتطفات عديدة من تاريخ المذهب الإباضي الفكري والاجتماعي عبر القرون الأربعة الماضية

Notes

- British Library, Or 9406. ↩︎

- On extant manuscripts, see M. Custers, Ibadiyya: A Bibliography (vol.2), pp.163-164. ↩︎

- Hūd’s tafsīr draws on the earlier work of Yahya b. Sallām al-Basri. See: Miklos Muranyi, “The Tafsir of Hud b. Muhakkim al-Hawwari (d. in the 2nd Half of the 3rd/9th Century) and Yahya b. Sallam al-Basri (124/742-200/815): A Synoptical and Intertextual Approach” in Local and Global Ibadi Identities, ed. Yohei Kondo and Angeliki Ziaka, Studies in Ibadism and Oman 13 (Hidelsheim: Georg Olms Verlag, 2019), pp.41-56. ↩︎

- Fihris makhṭūṭāt al-maktaba al-Bārūniyya bi-Jarba (Ghardaia: Jamʿiyyat Abī Isḥāq Iṭfayyish, 2018).[Catalog of the El Barounia Library], nos. 172, 185, 191. ↩︎

- P.M. Love, Jr. The Ottoman Ibadis of Cairo: A history (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009254267 ↩︎ - Bin Ya’qub MS 20, “Sharh al-jahhālāt”, copied by Muhammad b. ‘Ali b. ‘Abd al-Rahman b. Mashishi (dated 1 Muḥ 1037 / 12 Sep 1627). Library of Shaykh Sālim b. Ya’qūb, Jerba. ↩︎

- The first is “Hashiya ‘ala kitab al-wad'” Makt. al-Khalīlī, 119 (dated 15 Muh 1114 / 21 Jun 1702). The second is BNT A-MSS-22749, a copy of the Kitāb al-īdah (dated 7 Rab II 1082 / 12 August 1671). ↩︎

- The two texts are part of a composite manuscript in the Bin Ya’qub Library in Djerba (Bin Ya’qub MS 57). ↩︎

- On the Bārūniyya Press, see: Martin H. Custers, Ibāḍī Publishing Activities in the East and in the West, c. 1880-1960s: An Attempt to an Inventory, with References to Related Recent Publications. (Maastricht: n.p., 2006), p.5-24. ↩︎

- These details were provided Dr. Michael Erdman at the British Library. ↩︎

- On Yahuda, see: Evyn Kropf, « The Yemeni manuscripts of the Yahuda Collection at the University of Michigan », Chroniques du manuscrit au Yémen [En ligne], 13 | 2012, mis en ligne le 17 décembre 2012, consulté le 14 août 2023. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/cmy/1974; Efraim Wust. 2016. Catalogue of the Arabic, Persian, and Turkish Manuscripts of the Yahuda Collection of the National Library of Israel Volume 1. Catalogue of the Arabic, Persian and Turkish Manuscripts of the Yahuda Collection of the National Library of Israel. Leiden: Brill. ↩︎