As I begin a new book project on the history of Ibadi communities from the Jebel Nafusa in Libya, I have begun compiling data and accounts of private libraries in the region. This has included a survey of manuscripts from 30 different collection catalogs and surveys, which I was able to carry out using both recent documentation initiatives in the Jebel Nafusa and the rich collection of materials housed at the Ibadica Research Centre in Paris, France, while supported by a short-term grant from the fabulous Fondation maison des sciences de l’homme (FMSH) during summer 2022.

بما أني بدأت كتابا جديدا حول تاريخ جبل نفوسة بليبيا، بدأت أيضا جمع بيانات حول المكتبات الخاصّة والمخطوطات الموجودة تاريخيا في تلك المنطقة. في ذلك الإطار، قمت باستطلاع على 30 فهرس للمخطوطات اعتمادا على مبادرات مؤخّرة في الجبل وأرصدة مركز ايباديكا للدراسات والبحوث حول الإباضية الثمينة في باريس في فرنسا وذلك بدعم من مؤسّسة “دار علوم الإنسان” في صيف 2022

The majority of these catalogs relate to collections located outside of the Jebel Nafusa, especially from the Mzab Valley in Algeria and the island of Djerba, Tunisia. The reason for this is that there have been very few systematic surveys of manuscript collections in the region to date. As it happens, Nafusi copyists are actually easier to identify when they copying were outside the Jebel, since it was then that they self-identified their origins through their nisba in manuscript colophons (al-Tandinmīrtī, al-Kabāwī, etc.).

تتعلق أغلبية الفهارس بالمكتبات الموجودة خارج جبل نفوسة وخاصّة في وادي مزاب في الجزائر وجزيرة جربة في تونس لأنّ دراسات حول المكتبات النفوسية حتى الآن لا تزال نادرة جدا. ولكنه في الحقيقة، من الأسهل أن نعرّف بناسخ نفوسي عندما كان ينسخ مخطوطا وهو خارج الجبل لأنّه يذكر نسبته في حرد المتن في المخطوط (مثلا “التندنميرتي أو الكباوي) بينما قد لا يذكر تلك النسبة عادة وهو لا يزال في الجبل

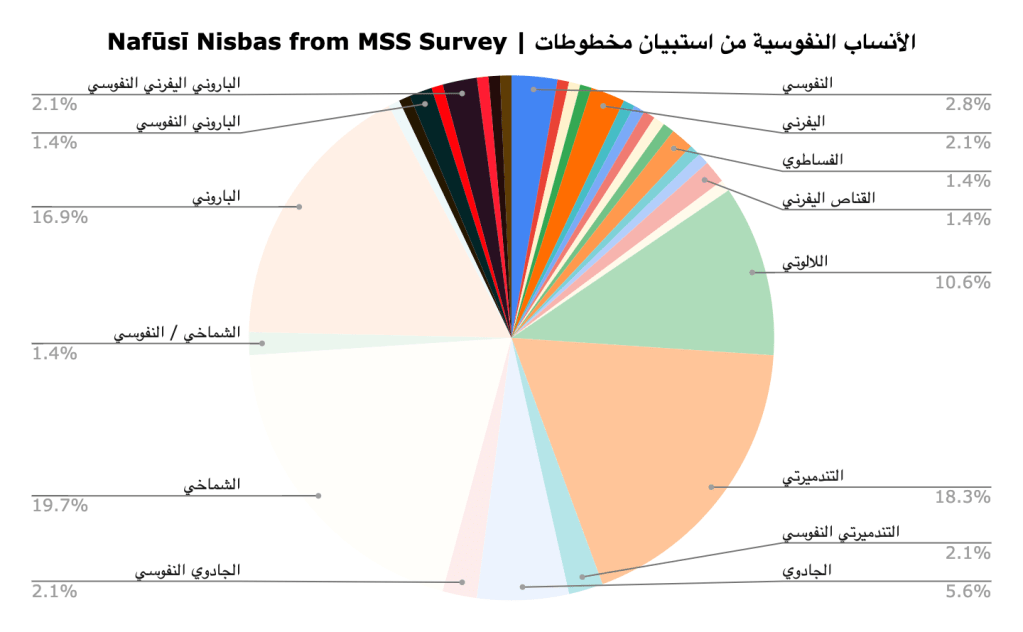

Here is the visualization that summarizes the results from the survey:

هذه الصورة تلخّص نتائج الاستطلاع على الفهارس والدراسات السابقة

There are some problems here that stand out, but they are no different from those raised by the use of nisbas in any research context, really:

تظهر فورا بعض المشاكل ولكنها لا تختلف تلك المشاكل عن التحديات في استعمال الأنساب في سياقات أخرى للبحث :ـ

- al-Bārūnī , al-Tandinmīrtī, al-Shammākhī, al-Jāduwī are all nisbas that have been used by copyists from the island of Djerba over a span of several centuries, which makes it difficult to determine whether they are from Jebel Nafusa or have ancestry from the Jebel | بعض النماذج من النسبة مثل الباروني والتندنميرتي والشماخي والجادوي تنتمي أيضا إلى عائلات في جزيرة جربة منذ قرون ولهذا هو من الصعب أن نحدّد أصله الناسخ القريب إلى جربة أو الجبل

- Even in cases where we might be sure that “al-Bārūnī” copyist comes from the Jebel Nafusa, it is hard to say where precisely since the al-Bārūnī family is one of the most prominent and, as a result, the most widespread | حتى ولو كان من المتأكد أن “الباروني” نسبة لناسخ من الجبل، من الصعب جدا تحديد قرية الأصل لأنّ العائلة منتشرة

- Many names have multiple nisbas, so deciding which is where they come from originally (“nasaban“) versus where they live (“maskanan“) or where they simply spent a long time is difficult to know for certain | كثيرا ما نجد أن النسّاخ لهم عدّة أنساب ولهذا هو من الصعب أن نميّز بين “نسبا” و”مسكنا” من خلال حرد المتن فقط

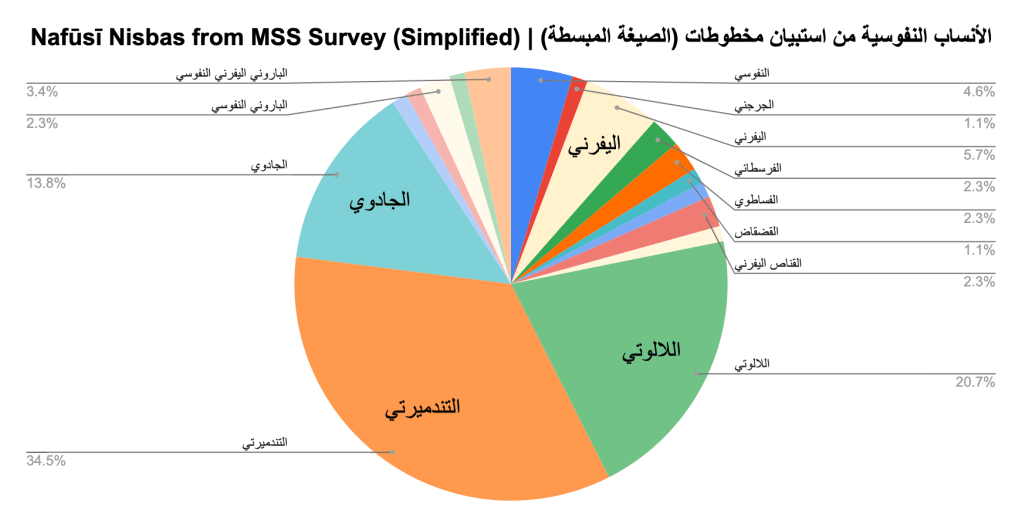

More revealing, I think, is the same visualization with some of the more ambiguous names removed, showing the prominence of four clearly Nafūsī nisbas: al-Yafranī, al-Jāduwī (also Djerban), al-Lālūtī, and al-Tandinmīrtī (also Djerban). Each of these nisbas refers to a specific area in the Jebel, which helps identify some clear centers of learning, or at least communities of scholarship, moving east to west: Yafran, Jādū, Tandmīra, and Lālūt (Nālūt).

في نظري، الصورة نفسها بدون الأنساب غير المحدّدة أكثر عابرة لأنّ أربع أنساب تظهر بارزة: اليفرني والجادوي واللالوتي والتندنميرتي. كل من هذه الأنساب تدلّ على منطقة معيّنة في الجبل وهذا يلقي الضوء على بعض المراكز للعلم (من الشرق إلى الغرب): يفرن وجادو وتندميرة ولالوت (أي نالوت)

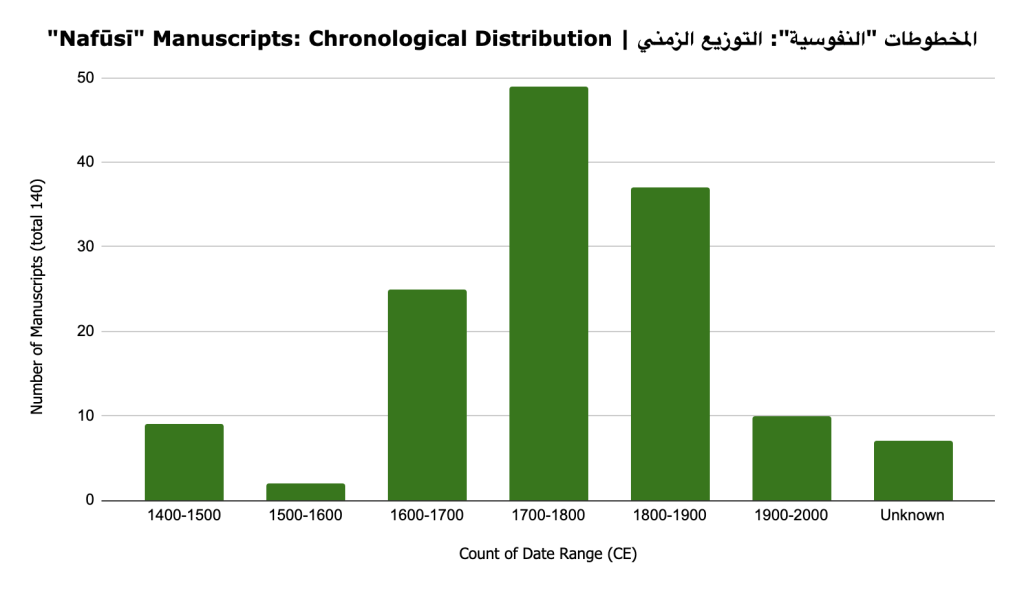

As a separate exercise, I also visualized the chronological distribution of the manuscripts, either based on the catalog’s estimate or, in a few cases, physical indications like watermarks :

تصورت كذلك التوزيع الزمني للمخطوطات نفسها اعتمادا على المعطيات في الفهرس أو بعض الدلائل المادية مثل العلامات المائية

Following a larger pattern of Ibadi-Maghribi manuscript production, the clear majority were copied from the 17th-19th centuries, with the 18th century being the most prominent. The next step will be to find a way of effectively visualizing those two sets of data, to look if there is a correlation between nisbas and specific time periods.

مثل أغلبية المخطوطات الإباضية المغاربية، صنعت الأكثرية خلال الفترة الحديثة بين ق17 -19م ويظهر القرن 18م أهمّها. الخطوة التالية: محاولة ايجاد طريقة لرسوم هذه البيانات معا (أي الأنساب والزمن) لنكشف عن أية علاقة بين أنساب وفترات زمنية معيّنة